Religious institutions and community organized gatherings are often assumed to be sustained by the strength of the participant’s belief in their respective creed. How else could such monumental temples and flyers of abbreviated doctrine persist in the culture if not for the firm, unflinching faith of the believers? In following, I will examine religion from a memetic perspective and suggest that the above assumptions are in fact false. I will argue that, for religious memes to ensure the fidelity of their transmission between hosts, they need not be believed in. Instead, as a side effect of how ideology operates today, religious memes function socially as a belief through others, which will rely in reference on Slavoj Žižek’s theory. Before reaching this conclusion, I will briefly explain how memes propagate according to Richard Dawkins and then refer to Daniel Dennett’s view on religious professing to explain why religious belief-memes are increasingly lacking belief.

Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene describes a concept of cultural replicators which he calls memes. What a gene is to biology, a meme is to ideology because both memes and genes follow the rule of differential replication. This means that whenever a meme is copied, it is slightly varied enough to ensure the survival of the next batch of its kind in the cultural landscape. For example, a person might reinterpret a religious parable in a way that is compatible with evidence that contradicts the traditional interpretation. This is what happened when Pius XII had to renounce his dismissal of evolution half a century after the fact and acknowledge that it is a legitimate hypothesis in the face of the evidence piling up. The Catholic Church meme could now ensure the transmission fidelity of its hosts despite the competing and growing Evolution meme.

Essentially, memes are units of ideas or information that are transmitted throughout culture by way of using human brains as “vehicles.” Computers are also another example of a vehicle for memetic evolution and Dawkins describes meme as “leaping” from brain to brain or from brain to computer and back. However, memes don’t actually “leap” like a frog does: the content is transmitted in a variety of ways, including books, audiotapes, conversations, social media, advertising, and so on. As much as the physical basis changes, the message remains sufficiently unchanged since what is being replicated is pure information. What is revelatory about the concept of memes is that it allows us to understand the adaptations and revisions in culture as happening with or without deliberate, foresighted authors. Dennett offers natural languages as examples of un-authored memes; “The Romance languages — French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and a few other variants — all descend from Latin, preserving many of the basic features while revising others.” (Dennett, p.78)

It will be helpful to briefly trace the origins of religious memes to their roots to understand how they have adapted to the current ideological climate. Dennett outlines two main biological factors that are responsible: our adopting an intentional stance and our tracking of tendencies in the environment. The intentional stance is when an animal treats something else as an agent with beliefs and desires. This is something that we and animals do naturally without needing to be taught since conceiving of competing agents is an indispensable skill for survival. Though, our self-awareness has greatly complexified our intentional stance compared to that of animals. Language has given us the ability to contemplate things no longer present to our senses and consequently has “brought into focus a virtual world of imagination, populated by the agents that mattered the most to us, both the living but absent and the dead who were gone but not forgotten.” (Dennett, p. 114) It is in this domain that memes propagate and hope for the afterlife is fostered. Dennett suspects that all mythological creatures, such as fairies, gnomes, monsters, etc., are residual “agents” that were hypothesized by our ancestors.

Tracking the tendencies of designed things -living or “artefactual”- is another useful survival skill though it can be over excessive so as to confirm inaccurate hypotheses. For example, a primitive person might ponder what causes weather changes. One day while dancing it might have happened to rain, and it would be natural for the subject in question to attribute a causal relation to his actions and the rainfall. The more times that this coincidence occurs, the more the thought reoccurs in his mind, either idly or deliberate, and a proto-meme develops — one which will spread in the culture the more people he persuades to it. Similarly, natural phenomena or apparent exceptions to the laws of nature, known as miracles, would have been chalked up to the doing of a supreme being. “Put these two ideas together — a hyperactive agent-seeking bias and a weakness of certain sorts of memorable combos — and you get a kind of fiction generating contraption.” (Dennett P.120)

The last genetic factor that ensures fidelity of memetic transmission is what Dennett calls the “information superhighway” between parents and children. Since it is in the genetic interest of the parents to honestly inform their children to equip their minds with as many insightful advantages as possible, children are genetically predisposed to trust the instruction they receive. This pathway of information transferring is susceptible to “hijacking” by a meme that will benefit. With the biological foundations in place, I agree with Dennett that with the rise of agriculture (which involved the domestication of animals and plants) certain self-sustaining memes of folk religion were also domesticated by people, thus becoming dependent on a steward. One can imagine that in the transition from living in nomadic tribes to residing in enclosed, isolated settlements, a similar information highway was formed between the ruler and his subjects — since they would depend on his rulership for food, protection, and employment. Today, these information pathways maintain fidelity in relations between, say, a politician and his or her supporters, a pastor and their congregation, or teacher and their students.

I theorize that as memes became stewarded, the amount of potential risk and reward regarding who benefits (us or the memes) also increases. Even in today’s context, wild-memes of pop-culture that circulate the interwebs are relatively non-harmful or non-beneficial. We might scoff or laugh, but then move on. But, stewarded memes — memes whose propagations are deliberately maintained by human guardians and financial bodies — are much more persuasive in their message and cunning in their tactics. Dennett notes one tactic; “accepting inferior status to an invisible god”(p.172) gives more credence to the authority of someone supposedly representing that god. Another dangerous stewarded meme today, Scientology, employs a financial incentive on its hosts to remain committed as they must pay a fee to read each new chapter of its holy book. These are examples of the risk, but Dennett thinks that reward is also possible with stewarding memes in that for all the good religion does “something we could devise might do as well or better.” (Dennett, p.55)

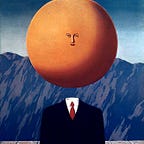

It is hard to identify all the individual religious memes that spun out from domestication since there is so much overlapping between them and constant variation. For example, Jesus’ beard is a fashion meme that might appear at Halloween, the cross is a symbolic meme appearing in jewelry, the crucifixion is an artistically referenced meme by the likes of Salvador Dali and Andres Serrano, and the supposed moment it happened is a historical meme about the calendar. On and on, the broad picture of the Christian meme blurs with so much intersection, and this is just one of many. For this post, the memetic aspects of religion I wish to focus on are:

1) The host’s internal state of believing (or at least their professing to believe.)

2) If a host’s perception of another person’s belief is enough to ensure the fidelity of memetic transmission, even if the host doesn’t really believe.

For the first point, I will assume in principle that actions other than speech acts are typically better evidence of what the person really believes over any words she might say. Now, “the transition from folk religion to organized religion is marked by a shift in beliefs from those with very clear, concrete consequences to those with systematically elusive consequences — paying lip service is just about the only way you can act on them.” (Dennett, p.227) In other words, the veracity of folk-religious-beliefs was more easily verified than the now institutionalized-beliefs. For example, if you really believe that the rain god won’t send rain unless you sacrifice an ox, you sacrifice an ox. Someone not sacrificing an ox obviously doesn’t believe that. But Lip-service is a much trickier thing to go on as evidence for the state of belief, especially since professing one’s belief is a requirement for institutional employment as a religious teacher. Paul says in his letter to the Corinthians: “Preaching the Gospel is not a reason for me to boast; it is a necessity laid on me: woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel!” (1 Corinthians 9:16).

How many of those paying lip-service would renounce the faith if held at gunpoint? Though the test is too extreme to conduct, I suspect many. Moreover, even though lip service is required, it still isn’t enough: you must firmly believe what you are obliged to say. But how is this possible considering that professing is a voluntary action whereas belief is not? You can’t force yourself to believe. “Cardinal Ratzinger’s Declaration offers some help on this score: “Faith is the acceptance in grace of revealed truth, which ‘makes it possible to penetrate the mystery in a way that allows us to understand it coherently.” (quoting John Paul II’s Encyclical Letter Fides et Ratio, Belief in Belief) The advice offered is to believe that others have been lucky enough to receive divinely revealed truth, and if you hold this belief you just might be lucky enough to one day!

Religious belief, in its institutional form, is mostly no longer a subjective, first-person belief, but rather, a belief in the belief state of someone else. This is an ingenious adaptive strategy by the religious meme, allowing it to survive even in a culture of increasing cynicism.

This variation in belief isn’t that surprising if we examine other ideological memes that have undergone a similar formula. I will briefly cite two examples given by the Slovenia philosopher and psychoanalyst Slavoj Žižek. First, consider the meme of Santa Clause, a fairly global cultural myth. The parents go through the ritual of Santa Clause since their children (are supposed to) believe in it, and they don’t want to disappoint them. But, if you question them whether or not they believe in Santa Clause, they will say “Of course not, we buy the toys for the kids.” If you really question the kids if they believe in Santa Clause, their answer (more consistent the older they get) is “No, we pretend to believe so as not to disappoint our parents.” Here is a belief that continues to function despite not being believed in by either side. It may largely be because the meme has attached itself to the economic cycle of consumerism — Christmas being the largest economic stimulus for many nations around the world as sales increase dramatically in almost all retail areas. (Statistica, US Christmas Season — Statistics & Facts.)

Another ideological phenomenon similar to religious belief is that of televisions canned laughter: when the soundtrack of a comedy series plays a recording of an audience laughing. Žižek writes “in the evening I come home…and watch Cheers, Friends, or another series; even if I do not laugh, but simply stare at the screen, tired after a hard day’s work, I nonetheless feel relieved after the show — it is as if the TV-screen was literally laughing in my place, instead of me.”(Will You Laugh for Me, Please. Para,4) The recorded laughter doesn’t actually provoke the viewer to laugh but, much more radically, laughs for the viewer. In the same way, the religious preacher at the pulpit believes for the congregation just as the television show laughs for the viewer. The following passage of Žižek’s is worth quoting at length:

And, furthermore, is this need to find another subject who “really believes,” also not that which propels us in our need to stigmatize the Other as a (religious or ethnic) “fundamentalist”? In an uncanny way, some beliefs always seem to function “at a distance”: it is always ANOTHER who believes, and this other who directly believes need not exist for the belief to be operative — it is enough precisely to presuppose its existence, i.e., to believe in that there is someone who really believes.

In conclusion, I claim that more and more religious memes are adapting their element of belief so that the doctrines are not believed in by the subject, but only in relation to another’s supposed belief. Whether or not any religious person actually believes themselves is now irrelevant to ensuring the fidelity of memetic transmission and propagation between hosts. It is unclear whether these memetic changes are more beneficial to the hosts or the memes, but it is nonetheless something to be aware of since, as per the above passage, it may lead to stigmatizing the Other as well as robbing an individual of genuine, experiential understanding.

References:

Dennett, Daniel C. Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Penguin, 2007

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Žižek, Slavoj. Will You Laugh For Me, Please? Published by “In These Times” July 18th, 2003. Retrieved from: http://inthesetimes.com/article/88/will_you_laugh_for_me_please

Statistica. US Christmas Season — Statistics & Facts. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/topics/991/us-christmas-season/