One of the most famous passages of Zhuangzi concerns a dream in which the author imagines himself to be a butterfly, and upon wakening, cannot distinguish whether or not he was dreaming of being a butterfly or if “he”was a butterfly dreaming of being him. The dream is recounted in the third-person perspective, making the identity of the subject all the more elusive. The difference between these two identity states, and how to distinguish them, is referred to as “the transformation of things” int he last line of the passage. Here, I will interpret the meaning of this passage in light of Zhuangzi’s perspective on death, which shares the theme of transitioning between states, an with reference to other contemporary research, conclude by arguing for a theory in which identity is a byproduct of the clinging mind.

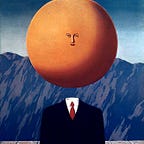

One night, Zhuangzi dreamed of being a butterfly — a happy butterfly, showing off and doing as he pleased, unaware of being Zhuangzi. Suddenly, he awoke, drowsily, Zhuangzi again. And he could not tell whether it was Zhuangzi who had dreamt the butterfly or the butterfly dreaming Zhuangzi. But there must be some difference between them! This is called the “transformation of things.”[1]

The passage begins in Zhuangzi’s dream, in which he no longer identifies as, nor remembers the wants or needs that come with, being Zhuangzi. His subjective point of view is of a butterfly fluttering about for its own sake, impressed with its ability to do so. Then, Zhuangzi awakes, and upon becoming aware of his own body and bed, his consciousness re-assumes identity with Zhuangzi. But he wonders, is there a difference between the phase of waking up and re-assuming identification with Zhuangzi, and falling asleep and assuming an identity with a butterfly or whatever other creatures’ perspective we may imagine? In short; what is the distinguishing factor?

If there isn’t any, then who is to say that their waking life isn’t but the dream of a butterfly? This is the paradox that calls into question his sense of self. Furthermore, this is all considered from a narrator’s perspective, who isn’t necessarily Zhuangzi, allowing the reader a more detached or objective consideration of this transition between identities. In other words, the reader cannot say, “well, it is Zhuangzi recounting the dream, so the person in question must be Zhuangzi.”

The haziness of most morning’s waking moments is all too familiar for most people. We dream we are not ourselves, and we dream we are in wild and unfamiliar situations. We may even have a dream within the dream we are dreaming, known as false awakening, causing us to experience the sensation of waking-up twice. What these widely common-experiences all share in common is a reliance on reflection and memory to anchor ourselves to a fixed, essential identity — the person we remember ourselves to be upon awakening. Thus, part of the paradox Zhuangzi presents is the question of how we fix our consciousness to an identity. And there are two senses in which this question can be unpacked: first, how do we know that we (the essential identity) are dreaming? And second, is the essential identity that we fix to itself a dream?

Considering the first sense — how do we know that we are dreaming — I am reminded of a famous episode of Batman: The Animated Series titled “Perchance to Dream.”[2] In it, Batman wakes up as Bruce Wayne but realizes the world has been turned on its head. For one thing, he isn’t Batman anymore, and his parents, long assumed to be dead, are alive and well. Bruce is unable to accept the reality he has awoken into as real because it clashes with what he knows about his reality, namely, the details of the essential identity he is fixed to. But it’s not until he opens a newspaper and sees nonsensical symbols instead of words that he realizes he is in a dream — a dream conjured by the evil Mad Hatter. Bruce reasons that “because reading is a function of the right side of the brain, while dreams come from the left side,” then it should be impossible to read while he’s dreaming.

Although Wayne’s detective work might not have been perfect, there is research to support his line of reasoning. Ernest Hartmann, Ph.D., published a seminal paper on what we do and don’t experience in our dreams, entitled “We Do Not Dream of the Three Rs,” (referring to reading, writing, and arithmetic) and found that less than one percent of the people he surveyed experience them in their dreams.[3]

Being aware of things that are almost impossible to do in a dream, which we have no trouble performing in our ordinary waking state, can be reliable way to verify if we are currently in a dream. In this way, we can test whether or not the identity we are currently fixed to is the real one — the one we are familiar with in waking life. But what about dreams where we forget ourselves altogether, as in dreaming we are a butterfly? If we are no longer anchored to our fixed, essential identity, but instead become momentarily anchored to a new, perhaps nonhuman, identity, or to nothing at all, then what exactly is the we to which we refer that is common between those states? This is the crux of the second sense of the question of fixation, since if there is nothing common between them, then it would seem identity is altogether illusory.

I will refer to dreams of this sort as vicarious dreams since they share a superficial resemblance to our imaginative abilities to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. That is, they are similar to when we imagine what life might be like in someone else’s position, but different in two ways. First, they do not frame the new identities thoughts or experiences in relation to, or as diverging from, our own. Secondly, they do not retain the perspective of the essential identity in addition to the imagined one.

It is the very absence of the reference point of an essential identity in relation to imagined or dreamt identities that provokes the insistent line in the passage: “but there must be some difference between them!” I believe Zhuangzi writes this line sarcastically to paraphrase the panic of the clinging mind, or what is sometimes called the egoistic mind, which wants to identify with one identity but cannot do so without a continuous subject. In other words, to say that the mind has a tendency to cling to an identity, is to say that the subjective awareness of being alive as identity X, can be mistaken for being identical with X. This could be considered a mistake under a theory of personal identity which does not equate person-hood to a particular body nor to a particular psychological-continuity. After all, we may inhabit different bodies or psychological-continuities in dreams as a conscious subject. It is that very conscious subject, apart from yet enacted through the particular physical or psychological states, which is the essential “I.”

Therefore, Zhuangzi isn’t saying that the problem lies in drawing a distinction between the various transformative phases we might inhabit (being a butterfly and a person are quite different modes of being); rather, the fault is when the essential “I” tries to bridge those phases by relying on details of semantic or episodic memory. It cannot do so because memory is ultimately a feature of the physical and psychological properties of the identity which the essential “I” (mistakenly) identifies with; they are not properties of the “I” itself. To better understand why the distinction between waking and dreaming is a false dichotomy, it is useful to compare it to another false dichotomy, which Zhuangzi illustrates: life and death.

There are two main passages that illustrate how Zhuangzi regarded death. The first recounts his behavior after his wife’s passing, “squatting down, beating on a tub, and singing.”[4] When questioned if he was misbehaving, Zhuangzi replied, “…something changed and there was qi. The qi changed and there was form. The form changed, and there was life. Today there was another change and she died. It’s just like the round of the four seasons: spring, summer, fall, and winter.” Clearly, for Zhuangzi, death isn’t something to fear, let alone mourn. It is the next stage in a natural process of transformations where one state of existence is exchanged to assume another. He then says, “She was resting perfectly at home, and I followed her crying, “Wah-hah!” It seemed like I hadn’t comprehended fate. So I stopped…”[5] Here, “home” refers to the state of qi which his wife has returned to and from which all life sprouts; the “vital life-force” as it is sometimes translated, that binds all life together. His sadness crying was provoked by his inability to retain his wife in the form he had grown accustomed to. As soon as he accepted her transition into a new state, as part of the natural course of change, his sadness also ceased.

The second passage on death concerns the moment when Zhuangzi himself was about to die. After he refuses to be buried in a casket, his students insist that they are “afraid the crows and kites will eat (him).” To this, Zhuangzi gives a colorful response; “Above ground, I’ll feed the crows and kites. Below I’ll feed the crickets and the ants. Stealing from one to feed the other would be awfully unfair.”[6] The startling reaction this wry statement may provoke is quite telling. The fact that people regularly wish for their bodies to be neatly buried and preserved after death after they will no longer have any use for it, is indicative of the lengths the mind will go to cling to an identity. Here, Zhuangzi has no attachment or investment in any particular identity state and is thus willing to leave his body and let it be used towards the survival of other creatures as he transitions into a new state, as is the natural course of all things.

To conclude, the false dichotomy between life and death that Zhuangzi sees is very similar to the one between waking and dreaming — or for that matter, between any segmented states in a series of transformations. By clinging to the hope of some essential, indivisible self that persists across transformations, Zhuang Zhou ensures that transformations will sow sadness, doubt, and loss. Change is inevitable, and so to smoothly transform between things, we must embrace each state’s current abilities and limitations and inhabit them fully, since ultimately that’s really all we ever have, and all we really are. “Step aside, and leave the changes. Then you will enter the oneness of the vacant sky.”[7]

References

[1] Zhuangzi, p. 244

[2] 26th episode of Batman: The Animated Series. It was written by noted horror author Joe R. Lansdale and originally aired on October 19, 1992.

[3] Hartmann, E. We Do Not Dream of the 3 R’s: Implications for the Nature of Dreaming Mentation. Dreaming 10, 103–110 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009400805830

[4] Zhuangzi, p.247, Chapter 18

[5] Zhuangzi, p.247, Chapter 18

[6] Zhuangzi, p.250, Chapter 32

[7] Zhuangzi, p.241 Chapter 6